Sure, you can’t will yourself out of a cold, but emotions and disease are more intricately connected than we’ve been led to believe.

Nestled at the top of a low mount, overlooking the wide-armed ocean, lay the remains of the Asclepion; an ancient sanctuary, dedicated to the Greek god of healing, Asclepius. Pilgrims would travel to the Asclepion from afar seeking respite for all sorts of ailments.

Physician and priest would work together to ease the burdens of disease. Therapies would include water from the natural spring, a bath, a trip to the gymnasium, a clean diet, herbs, surgeries, teas, dream interpretation, and activities to calm the mind such as prayer, music and sleep. The ancient Greeks believed intuitively, some might argue ignorantly, that the mind and body were intimately connected.

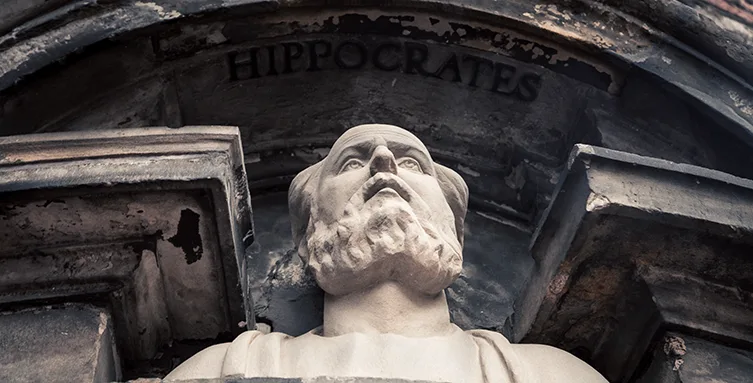

Hippocrates, who’s attributed the title “father of medicine” and whose legacy has largely endured through the Hippocratic Oath often employed by medical schools today, was born on the island of Kos around 460 BC. He is said to have received his medical training here at the Asclepion.

Hippocrates was a thought-leader. He attributed disease to natural, real causes, disentangled from deities and superstition. He also believed that health lay in a balance and promoted a person-centric approach to healing.

Whilst progressive and honourable for his time, some of Hippocrates practices were notably antiquated. A treatise, The Nature of Man, accredited to Hippocrates’s son-in-law Polybus, recounts the concept of humorism.

The human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed.

The theory of the four humors – blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile – became a popular medical system for understanding the human body, medical treatment and a person’s temperament. The theory explained disease as an imbalance that was inextricably linked with emotional state. For example, a person who was melancholic, depressed, had excessive black bile and was treated accordingly.

When all of these elements are truly balanced and mingled, he feels the most perfect health. Illness occurs when one of these qualities is in excess or is lessened in amount or is entirely thrown out of the body.

On the Constitution of Man. The Four Humours, Part IV.

Medical treatment focused on balancing the four humors. As such, humorism brought with it the ‘curative’ practice of bloodletting. Initially designed to assist the body to re-establish balance or homeostasis, bloodletting became a popular – potentially dangerous – medical treatment up until the 19th century.

Overtime, critics of such antiquated practices amassed and with the advent of anatomical dissection, pathology and the microscope, the concept of emotions and their relationship to disease understandably fell into the domain of irrational and magical thinking. “If you couldn’t see it or quantify it, it wasn’t real” became the enduring, unspoken dogma of medical science.

In the early 20th century, a “new” medical discipline emerged, designed to categorise the often intangible mind-body observations; that is, illnesses without any visible or physical explanations. This “new specialty” was labelled psychosomatic medicine. Overtime it accrued, among other conditions, chronic fatigue, chronic Lyme disease and hypochondriases. Although as a discipline nothing truly new, the advent of psychosomatic medicine highlights the expanding rift between the mind and physical disease.

As the Asclepions become barely discernible stones and rubble, the physicians and scientists of modern medicine became specialists. The lens through which patients were diagnosed and prescribed narrowed. Food was no longer medicine. Instead, dietetics was institutionalised and separated from medicine. Psychology developed with no concern for biochemistry and certainly not nutrition or physical activity.

By necessity, we have witnessed the modern, rising tide of the wellness gurus, the alternative medicines and the celebrity doctors. As the scientists and medical profession traded holism for stoic reductionism, the public sought to placate their intuitive emotional needs elsewhere. The success of the alternative practices may lie in this very process.

In recent years, I have observed a gradual shifting tide. Technological advancements and new thought-leaders are paving the way for the resurrection of mind-body medicine. We can now scientifically explore the interactions between emotions, neural pathways, neurotransmitters, genetics, and the immune and endocrine systems.

Stress is no longer just in the mind, but has a very real and measurable physical effect. IBS can be similarly relieved with diet, pills, baths and yoga. Epigenetics holds considerable promise for understanding how the mind can directly impact our genes and disease. Scientists are being roused to diversify and explore these interactions, and we are increasingly expanding our ideas about the gut-brain axis, psychoneuroimmunology and other emerging multi-disciplines.

Becoming multidisciplinary is increasingly cool and necessary for career scientists. In medicine, there are growing numbers of integrative doctors. Whilst this is positive progress for mind-body medicine, there remains a long way to go and as always in history, there will be division.

At least we can all agree that the mind and body are connected, rather intimately; that emotions do play a role in health and disease. We can measure the placebo effect; the psychology component of a positive therapeutic response to an intervention. By understanding these interactions in scientific language, we are entering a new and exciting age. We may finally begin to understand in biological terms the healing power of the ancient Asclepions. Unfortunately, true integrative health and healing people holistically is a long way off.

References:

Nicolle, L, & Beirne, AW. (2010) Biochemical Imbalances in Disease: A Practitioner’s Handbook. London: Singing Dragon.

Gimbel, S. (2011) Exploring the Scientific Method: Cases and Questions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Self healing, patents and placebo, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/emotions/self.html

Psychosomatic medicine, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/emotions/psychosomatic.html

Multidisciplinary Research: Today’s Hottest Buzzword? http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2003/01/multidisciplinary-research-todays-hottest-buzzword